Chrono

Weapon

Asia

Japanese

Sword

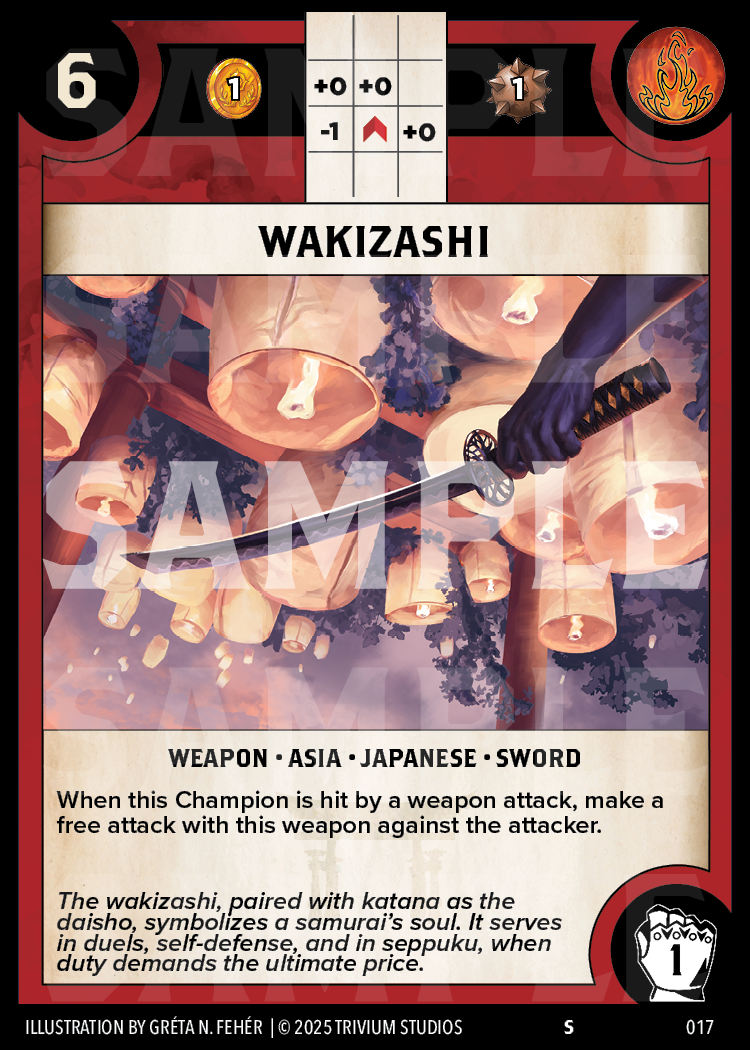

When this Champion is hit by a weapon attack, make a free attack with this weapon against the attacker.

The wakizashi, paired with katana as the daisho, symbolizes a samurai's soul. It serves in duels, self-defense, and in seppuku, when duty demands the ultimate price.

The wakizashi was the indispensable short sword of the samurai, a companion to the katana that embodied centuries of martial tradition, artistry, and cultural symbolism from the Muromachi period onward.

First appearing in the late 15th century, the wakizashi was defined by its blade length—generally between 30 and 60 cm—and its role as the smaller half of the daishō, the paired swords worn by samurai. The katana represented battlefield authority, while the wakizashi signified vigilance and personal honor. Its name literally means “inserted at the side,” reflecting how it was worn tucked into the sash (obi) on the left hip, always ready for use indoors or in close quarters. Unlike the katana, which was often surrendered at the entrance of homes or castles, the wakizashi remained with the samurai at all times, making it a constant companion and a visible marker of status.

On the battlefield, the wakizashi was more than a backup weapon. Its shorter length allowed for rapid draws and strikes in confined spaces, and swordsmiths often forged it with unique cross-sections and tempering styles to withstand intense combat. It was also used for grim duties: beheading fallen enemies to claim trophies, or in the ritual of seppuku, where its size made it the chosen blade for self-inflicted death to preserve honor. These associations gave the wakizashi profound cultural weight, intertwining it with the samurai’s code of bushidō.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), the Tokugawa shogunate formalized sword regulations, setting blade lengths for katana and wakizashi and requiring samurai to wear both. This codification elevated the daishō into a visible badge of class identity, instantly marking the wearer as a member of the warrior elite. The wakizashi also became a canvas for artistry: lacquered scabbards, silk-wrapped hilts, and blades etched with hamon temper lines or horimono carvings of Buddhist symbols. These embellishments reflected not only martial identity but also aesthetic refinement, blending weaponry with artistry in ways unique to Japan.

Variants such as the ō-wakizashi, approaching katana length, and the ko-wakizashi, closer to a dagger, demonstrated the flexibility of the form. Together, they bridged the gap between the long sword and the tantō, ensuring that samurai had weapons suited to every circumstance. Even after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when samurai privileges were abolished and sword-wearing curtailed, wakizashi continued to be forged as ceremonial or artistic pieces, preserving their legacy in Japanese craftsmanship.

Today, surviving wakizashi are treasured in museums and collections worldwide, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to private holdings. Each blade is a testament to the fusion of utility, honor, and artistry. The wakizashi’s enduring allure lies in its dual nature: a weapon of necessity and a symbol of identity, forever tied to the image of the samurai who carried it at their side.